Fire-Roasted Trout with Grilled Figs in Huck Out West // Cook Your Books

No doubt, I feel a kinship to Mark Twain. The summer of 1984, I went to Hannibal, Missouri, with my family. One hundred miles north of St. Louis, Hannibal boasts being the boyhood home to Mark Twain and the inspiration for Tom Sawyer's spelunking adventures and picket fence white washing and for Huck Finn's hogshead barrel sleeping. It was also the site of numerous family and school trips. But one trip stands out in particular.

Instructed to buy one souvenir, I lingered over plastic trinkets and snow globes and novelty spoons, I am sure. But something in me wanted more. I wanted something grown up, because I was feeling grown up. I was about to turn ten and I felt the weight of a full decade upon me. So I browsed the bookshop, tracing hard cover spines with my whole palms, and I settled on The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I still have this copy. The inside cover of the book boasts my name, the date (7-6-84), "Hannibal, Missouri" (in a handwriting that is distinctively mine still) and my name written again (with more flourishes this time) on a fancy bookplate depicting a unicorn rearing up, its hind legs perched atop the earth, a rainbow snaking through the celestial spheres, and a twinkling crescent moon. I was almost ten, and Mark Twain certainly would have been hometown proud.

Since then, I have taught this book many, many times, and it frustrates, delights, disgusts, and challenges me. It is the book of my youth, my adulthood. Hemingway even claimed that "All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn." So it came as no surprise that I snapped up Robert Coover's Huck Out West earlier this year, and tore through it.

And so Coover gets this world right. Tom, ever amoral, commands Jim's fate once again and Huck, ever the innocent abroad, records it all. However, Tom departs soon (headed east to study law in order to control the sivilized world when he can and rekindle whatever romance there was with the wealthy Becky Thatcher), and we find Huck alone, scouting for General Custer, bedding down in Deadwood Gulch, riding shotgun on coaches, wrangling horses on a Chisholm Trail cattle drive, and suffering an almost hanging for a trumped-up murder charge.

Given my project of cooking my books, I had plenty of food to choose from, including roasted horse meat (22), post-wedding beer with jelly and donuts (36), bread and coffee (54), buffalo jerky (113), corn bread and wild pig sausages (182), thin, brothy soup (211), Becky-Thatcher-offered butterscotch cookies (252), dried corn and desecrated fruit (284), and plenty of whiskey. Plenty of whiskey. Huck did not fall far from Pap's tree. He just knows how to hold his liquor better.

However, I chose fish (trout to be exact when crappie is called for, but I know you're willing to go along with me, right). A grilled fish on the frontier, pulled straight from the river and roasted over an open fire (with a rather long pull of whiskey), well, this just seems like the perfect meal for one out west in search of their very own Edenic paradise away from the ever-encroaching, swindling, "sivilizing" forces of the east, right? And so it is for Huck, who has come to see the simple processes of fishing and cooking as the act of making a home. He says, "When I rode Ne Tongo [his horse] into the little hid-away cluster of unpainted broke-down shanties and raggedy tents at the edge of Deadwood Gulch, nigh to cricks too fast and shallow for rafting, but prime for fishing--there was even a patch of sweetly clovered meadow beside the crick for Tongo to graze on--I knowed I was home. A place I could take my boots off all day long" (3-4). A bit of a dangerous place with a shallow but fast current. No more constraints of footwear. Just sweet clover and a prime creek and your munching horse.

And Huck goes on about this paradise (and I am going to quote a little more extensively here because this is almost homily):

I opened the smoke flap in the tepee and started up the fire, and then took my pole down to the crick to catch us some supper. Dusk's half-light is always prime for fishing. Hardly before I'd begun I had me a handsome black crappie close to a forearm long to go with the half-dozen panfish on my morning trotlines, some of them still snapping their tails about in a kind of tragic greeting when I hauled them up. I know it don't make them happy, but it seems only fair for us fellow creturs to give up our bodies to others' appetites. I don't want to get et by mountain lions, but I won't hold it against them" (15).There is a sense of ritual without pomp: the preparation of a fire, the knowledge of the land and its best times for fishing, a fortuitous capture. There is recognition of community with his fellow creturs. He cleans the fish, and he smokes from a carved stone pipe given to him by the Lakota people. "It was what I had for good luck when the world was mostly throwing bad luck at me. It was such moments as made me feel I'd finally come to the right place. Plenty grub and an easy life, ain't no bad thing.... (15) He recognizes it won't last, that at the next moment he could be mountain-lion dinner, but he relishes this time for what it is and when it is. And this time won't last (and he says as much, "At the same time, I misdoubted it would last" (15))--not in the novel, not in American history--so he urges us to relish these little moments of peace, even if they are singular and stolen, while we can.

Later, he says, "A river don't make you feel less lonely but it makes you feel there ain't nothing wrong with being lonely" (35). This river, these fish, this frontier without the sivilizing influences makes you feel there ain't nothing wrong with being by yourself, with being with only yourself. Sounds like a home to me.

That said, we were "this close" to making pancakes again. This was almost a post on the reconnection of friends (although ostensibly, it already is). There is a brief reunification with Jim, who makes a cameo appearance as the chuck wagon cook on a trail of missionaries searching for a fountain of youth, quite possibly in Montana, or hoping to join the Mormon trail. Calling Huck "Huck honey," Jim once again shows a love of Huck that he is perhaps not deserving of, if simply by association with Tom. Recognizing how "dog-hungry" Huck truly is, Jim puts together a stack of flap jacks (69-71). Together they let out unrestrained whoops, embrace deeply, share stories, and tuck into breakfast. However, this, like all other moments, cannot last. Distracted by the flirtations of woman who distracts herself with flirtations, Huck has to leave (and rather quickly) this particular trail ride and his beloved Jim, despite promising Jim he would not leave his side until they find Jim's wife and children. Another promise made. Another promise left unmet.

However, despite Huck's quickness to flight, this is, of course, a book about that companionship where which we can find a sense of home, a sense of connection beyond explanation.

Throughout much of the book, Huck's closest companion is Eetah, a Lakota Indian and another self-described misfit who was"having about the same trouble with his tribe as I was having with mine" (3). And their bond is strong--in part because Huck loves a story teller, and Eetah tells Huck Coyote and Snake stories, many of which Huck cannot understand but still appreciates. Coyote, that great trickster, has always fascinated and attracted Huck--no wonder, then, that he was and is so enamored of Tom, who enters into the novel at the almost magically perfect moment.

Oh and when he does, Tom lights this novel up. And we hate ourselves for that. Saturnine and amoral, Tom literally comes in hot, guns blazing, sharpshooting a lynching rope from the gallows just as the trap door opens, and thus saving an about-to-be-hanged Huck. But Tom's a gold-hungry imperialist, a murderer of Indians, a dominant and aggressive shaper of stories, a racist, and the consummate adolescent. He has never grown up, despite the oft-mentioned growing bald patch on the back of his head, and it seems unlikely that he ever will.

Undoubtedly, Tom is titillating in this book; his hyperactive antics drive a novel that is hardly concerned with plot beyond the picaresque, and he brings us narrow escapes and bawdy sex and horrific violence, all seemingly without consequences. And it is an thrilling, if harrowing, comment on our desire for excitement, for stories without endings, or repercussions.

I probably worry more that America today is making me think (or write) differently about late-nineteenth-century America. The story starts at the outbreak of the Civil War and ends with the Deadwood Gold Rush. This era, not the Revolutionary period, was what truly made us who we are. It was an adventurous time, but also one full of greed, virulent hatreds, religious insanity, the slaughter of war and its aftermath, widespread poverty and ignorance, ruthless military and civilian leadership, and huge disparities of wealth. Not a pretty history. But I hoped that Huck’s sympathetic and gently comical voice might make it bearable.Huck makes us want to see consequences for all of these actions--both personal and historical--that leave the vulnerable at the mercy of charismatic and unscrupulous leaders (Tom or otherwise). And in a world where these consequences don't come often, where stories are strung together with the most tenuous of connections, Coover presents us a world of Huck, Eetah, and Ne Tongo, who are trying to save what is worth saving. This is the world with the ability to sit with your closest friend and fellow misfit and with your loyal companion over some simple fish.

At other points in the novel Huck interrupts three men frying fish from Huck's trout lines (107), and he cooks fish for breakfast after hiding guns in his tent (138). But more importantly than not, just as the book opens with fish, so it closes with it. This is a ritual. A way to carve these little moments that Coover suggests don't last long but are the ones worth savoring. Otherwise, all we have is Tom commanding this unethical and almost pornographic world. Let's just have some fish by ourselves or with others. Let's just enjoy something caught with our own hands for the time being.

As the story progresses, through a series of Tom-instigated plot points--because Tom stars in his own story without regard to others or concern for the outcome--Huck is in the position to have to save Ne Tongo in order to go with Eetah to "where the war ain't" (291):

Then I spied a gnarly old miner with a shovel and a pan and a bottle he attended to regular. I went over and told him we was looking for a partner with a shovel, and he was happy to obleege. He says his name was Shadrack and he was from Ohio where he's been a farmer mostly till the grasshoppers et him out. I knowed Tom would a somehow got him to pay for the chance to shovel up the steps in the pit, but I was grateful just to have the shovel, and mostly let Shadrack lay off. Him and Eeteh nodded at each other without saying nothing, and Shadrack went down to the water with his pan to poke around, he didn't find no gold, but he catched a big fish, which he shared with his partners (292).Another fish caught, this time not by Huck. Another fish shared one's partners, even if they are not Huck and Eetah. Another community making a connection, deciding whom to include because they are your closest companions, and whom not to.

Ne Tongo is saved, he and Huck race "all the way to the sunset" (296) four pages later, and then Tongo leaves them, this time for good. So in rides Tom again, wearing white (both hat and gloves) and a red bandana tied around his neck, "so he warn't Tom so much as Tom's fancy of Tom" (297), ready to betray Huck (and by extension Eetah and Tongo). Huck, for a moment, holds his ground, knowing that "Tom was hurting and I was sorry, but I was hurting too. And I was worried about Eeteh" (299), whom any of Tom's friends could shoot without worry about retribution or justice. But Eetah's community comes to save Eetah and Huck. Not out of any allegiance to Huck, but out of allegiance to Tongo, who is a "spirit horse. God dog" (301). A friend of Tongo's is a friend of the Lakotas. A community. A set of partners.

And Huck invites Tom to join him to light out once again. Tom refuses and so Huck goes, leaving Tom behind. One community forged, another abandoned.

Finally, this book opens and closes with fish. Or at least the potential of fish. In a final chapter, as Eetah and Huck light out, no clear territory in mind, just away from Tom and his new moral order of constant worry of betrayal, Eetah tells the story of Coyote's talking "members," of which apparently he has multiple. Huck tells Eetah that he heard Coyote speak directly to him when he was on a wild 4-page ride with Tongo, and Eetah suggests that it was Raven, not Coyote, who spoke to him. Huck is confused, "lost again" (308), he admits, because he doesn't know who or what dismembered body part has been speaking to him. All he knows is that Coyote and his stories are truly Eetah's, not his. He is content enough knowing that there "was a crick down below us in the twilight without no prospectors on it, where we could probably fish up a supper." There they will make camp, drink whiskey, and "muddytate" on trickster tales. And so, it is without a doubt that Huck will make, if only for a moment, another Edenic home or another "right place," over fish, with his true friend--one without malice or motive.

And so, perhaps, should we.

------

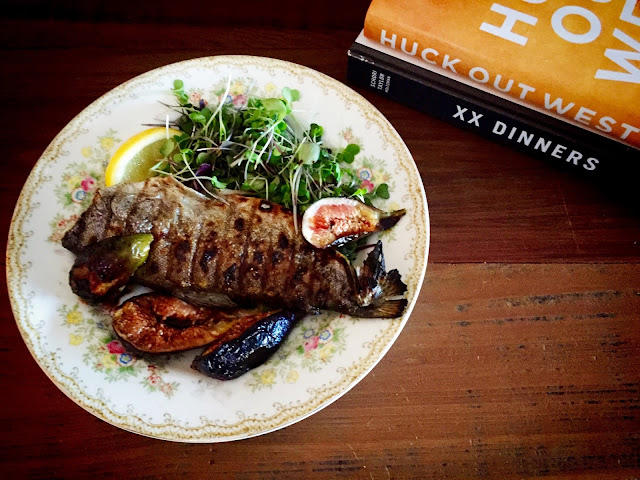

Fire-Roasted Trout with Grilled Figs

"I larded up a frypan and set it on the fire, throwed in some salt and the cleaned fish, and set back to enjoy an evening pipe... It was such moments as made me feel I'd come to the right place. Plenty grub and an easy life, ain't no bad thing..." (Huck Out West 15).Very liberally adapted from Twenty Dinners

A pretty little dish, this is as easy as can be, and rather economical. Every time we make fish, we say, "We should make fish more often." You can grill with or without the head (the husband chose to grill without the head). Be careful of bones, but seriously, this is worth a grill-firing-up. The figs are a sweet counterpoint to the unctuous skin. The smoke from the grill is the perfect and only necessary accompaniment to the fish, though the microgreens (or just a salad of mixed lettuces) are a nice touch. Twenty Dinners does a great job here making a perfect backyard Eden.

Yield

Serves 4

Ingredients

1/2 cup hazelnuts (optional)

12 fresh figs

grapeseed or vegetable oil

4 whole trout (about 1 pound each), cleaned and butterflied (ask your fishmonger to do this for you)

Extra-virgin olive oil

8-12 sprigs fresh thyme

4 bay leaves

salt

2 Tbsp balsamic vinegar

A few handfuls greens (or microgreens)

1 lemon, cut into wedges

Salt, pepper, and olive oil for finishing

Instructions

1. Prepare your fire and set up your grill. Allow the fire to get really hot--and the grill to be completely cleaned from the heat of the fire--then wait for it to burn down enough so it's a very hot be of coals.

2. Toast the nuts: When the fire is ready, set a small saucepan over the grill grate and allow it to heat. Toss the nuts and let them toast, until lightly browned and fragrant. Remove them from the pan and set aside.

3. Coat the figs with grapeseed oil. Coat the fish with a small amount of olive oil, both on the outside and inside the cavity. Stuff each fish with 2-3 sprigs of thyme, 1 bay leaf, and a pinch of salt; then lightly salt the outside. Arrange the fish and the figs on the grill, leaving enough room to flip the fish over when the time comes. Cook the trout for 3 minutes on the first side, then flip over with a thin spatula and finish for 2 minutes on the other side, or until the fish is just cooked through. While the the fish cooks, return the small saucepan to the grate. Add the balsamic vinegar and let reduce by half. Reserve.

4. When the fish is done remove it from the grill and let it cool for 3 minutes on a warm plate. Meanwhile, roll the figs around with a spoon so they don't overcook on one side. Remove the figs and toss them in a bowl with the reduced balsamic vinegar while still hot. Set aside.

5. Once the fish has rested, serve the fish whole, advising them to be aware of errant bones. Make a bed of greens on each plate and top with a few figs. Lay a trout on top of the figs and finish with a generous squeeze of lemon, a sprinkling of salt, the hazelnuts, and some olive oil.

Comments

Post a Comment