Spiced Plum Jam in The Constellation of Vital Phenomena // Cook Your Books

Lately, there haven't been many books that keep me up at 1 a.m. weeping on my couch. Lately, I have been arguing at book club that most 20th- and 21st-century novels (or at least the ones I have been reading) highlight the futility of community. Lately it's been hard to find books about connection or, let's face it, even meaning. Lately, such a viewpoint seems depressing, because it is not truly the viewpoint I actually take on the world. Lately, I have been looking for a book like this book.

In Anthony Marra's absolutely stunning debut novel from 2013, The Constellation of Vital Phenomena, one must be ready for the brutality and cruelty of the Chechen Wars. One must be prepared for the absurdity, betrayals, hopelessness, and horror of rape, torture, betrayal, land mines, and check points (it is not a book I would recommend lightly). And, yet, one must also be ready for humor, whimsy, and coincidence. For meaning and hope and beauty. For a sense of community and connectedness. It's kind of just the book I needed.

This book is big--not necessarily in page numbers (but it does clock in at 379 pages)--but it is big in scope. This plot is complicated, contains what feels like a multitude of coincidences, almost to the point of eye rolling. Then I realized that was a limitation on my part, not the book's. More on that in a moment. But let's look at a fraction of the plot.

The book opens with an abduction, with loss and brutality. Set in Chechnya between 1994-2004, this book is unrelenting. Eight-year-old Haava hides in the forest with a small blue suitcase as her father, Dokka, is taken by Russian soldiers in the middle of the night. They accuse him of aiding Chechen rebels, because an informant (a man he considered his friend) tells them so. A neighbor, Akhmed, also watches, afraid of what has happened to Haava as the soldiers set fire to her home. While the house burns, Akhmed finds Haava, and he brings her to a hardly-functioning hospital, where the sole remaining doctor, Sonja, almost single-handedly tends to the wounded. Sonja, who is an ethnic Russian born and raised in Chechnya, gave up a career in London to return to her sister, Natasha, who is recovering from enforced prostitution. Now, Sonja is consumed with grief as her sister has vanished in the wake of the Russian bombing of Grozny, and she has no emotional space to take in an orphaned child.

So that's the premise. Or at least the opening chapter.

Then the book continues with stories of gun-running neighbors, a military officer with a chest stitched with dental-floss, a one-armed security guard, multiple affairs, and a gun that holds together all of these characters coincidentally, tragically, and heroically.

Yet, more than any of the horrors of war is a sense of the power of one's stories, this sense of community, this sense that we are actually bound to one another, in spite or and sometimes because of cruelty and pain and betrayal. As heartbreakingly brutal as this book is, and it is, there is this beauty that permeates it all--from the poignance of Havaa dreaming of sea anemones on the night of her father is duct-taped and thrown into the back of a truck to the tender embrace of two men who spin and spin in the mud. That bond stems from a sense of purpose, of the commitment to one another, of the stories that we tell one another about the meaning we create in our own lives.

And, because of the nature of this blog and this project, I have to mention that there is food--all over the place: Akhmed and Havaa share black bread together on the road to the hospital (9); Sonja's sister Natasha drops an entire pot borscht, staining the Sonja's couch and providing a reminder of her sister's prolonged absence (32); Akhmed feeds broth to Ula, his bed-ridden and dementia-stricken wife (31); Sonja cooks Natasha potatoes and onions in a sisterly gesture of care (104); Natasha wistfully remembers starting her day with such simplicities as an alarm clock, breakfast djepelgesh, morning news, and a cigarette (180); the informer Ramzan trades cured meat for shotgun shells (233); in the mountains Dokka and Ramzan can eat freely, without the need to talk as their mouths are full of and satisfied by mutton (245); in contrast to the landfill pits where prisoners are taken, Ramzan has a fantasy of modern Chechen prisons that store banana peels, potato skins, and apple cores along with broken shoelaces, last-year's calendars, and deflated tires (257); the Chechen army comes to the hospital and tells of a commander who ate only antacids and an army that could only eat breakfast kasha (307); Ula used to take carrots from her mother's stew and feed them to her rabbits (327); Khassan taught his young son Ramzan to eat sunflower seeds, long before Ramzan is tortured and becomes a Russian informant (365). And so many, many cans of sweetened condensed milk or evaporated milk because nobody can access fresh milk, as it was the first to go in the food shortages (302); next to go were plums, cabbages, then cornmeal (302). And while there are stories here, and some of them are central, none stand out quite like the plums.

One character, Khassam--who is the scholar neighbor of both Akhmed and Dokka and disappointed father to the informant Ramzan--is trying, in some small way, to lay bare purpose, commitment, and meaning--from an historical perspective. Khassan publishes only a fraction of the 3,302 of pages he has written on Chechen history in a chapter entitled "Origins of Chechen Civilization: Prehistory to the Fall of the Mongol Empire." The only story that he can publicly tell is that of before his country was a country. This tome burdens him; he obsesses over it, as he wrestles with the decision of whether or not to kill his own son, Ramzan, for his son's turn as a Russian informant. Khassam resorts to writing, instead, the simple and private stories. Khassam knows, like us, that Dokka is doomed; he will be killed. Not in this book, but the ending leaves no doubt that it is merely a matter of time. In order to preserve for Havaa the stories that she, as an eight year old, will forget, that she is doomed to forget, just as Khassam is doomed to forget as a future sufferer of dementia, he writes down the stories of Dokka and Haava.

And the first story he writes involves a beautiful gesture and a plum. Allow me to quote rather extensively:

These are stray memories, plucked from the air. But if I closed my eyes and force myself to find your father, to truly find him, I would find him at his chessboard. In his forty years he lost only three matches. One was to you on your sixth birthday.

I would find him peeling a plum. You haven't forgotten, have you, how he peeled the skin with a paring knife? A dozen revolutions and the skin came off in a thin, unbroken coil, a meter-long helix. He transformed that skin of that squat little fruit, smaller than your fist, into a measurable length. Then he held the blade to the naked flesh and rotated the plum vertically. One half fell from the other, the clean so cut not even a filament clung to the seed. Pale pink beads dripped to the plate. If Sharik [Khassam's dog] was with me, the dog would contemplate his hands eagerly. But when your father finally let them fall within reach of Sharik's tongue, he tasted the disappointment of dry skin; your father wasn't a graceful man, but he could cut a plum like a jeweler.

He pretended to prefer the skin, and always gave you the flesh. You devoured the slices because you had to wash your hands before touching the chess pieces. It was a beautiful set, hand carved, purchased by your great-grandfather, before the Revolution, when a postal clerk could afford such intimate craftsmanship. He taught you to play chess, and on your sixth birthday, he let you win. Your father did many things in his forty years. Yet if pressed to recall his finest moment, I would chose to see him in the living room, with you, by the chess set peeling a plum. (131-2)

That skin is continuous, unbroken despite being peeled from the fruit. A stretch, perhaps, but much like the stories told within this novel. More obvious though is the description of the peel as a helix, which can only call to mind DNA, this connection of genetic material of one to another. And Dokka is masterful in peeling it, transforming the"squat little fruit," something ugly into something vulnerable in its "naked flesh" but also exquisite with its "pale pink beads." Further, there is something magical about the peel, which is over a meter long, coming from a fruit "smaller than your fist." This is a gesture of wonder and delight--a gesture that suggests even the smallest fruit holds this massiveness, just as the smallest stories or gestures hold within them a multitude of possibilities.

Dokka makes small sacrifices for Havaa (eating the skin while offering her the flesh), sacrifices she cannot understand or appreciate, as she is only six. She "devours" the plum, ready to wash her hands promptly, as she has other things on her mind rather than the beauty of her father artfully peeling a plum as a gesture to her. She has a chess game to play. The logic of the game seems--to her--paramount to the experience; for her there is nothing tangible to be savored here. However, Khassan sees instead the gift of the plum flesh and the ethereal offering of a father sitting with his daughter, letting her win at chess game played on a board purchased by her great-grandfather.

Most poignant and breathtaking about this novel is that the stories we tell are inadequate, not because there is no purpose or meaning, but because we cannot always know the full story. That there are stories outside our own that are as steeped in their own purpose that lend meaning to our own lives without us fully knowing how or why or when. And we lend meaning to those stories without realizing it either.

If we were to write the stories of our own lives, or better yet if someone, who knew the stories of all of the lives that have touched our own and we have touched theirs, were able to tell to those stories, too, then our stories would look coincidental and concentric. Like an unbroken, continuous peel of a story. And they would have an insight that we would not--perhaps because of our haste to move on (to wash our hands and get to the game of chess, perhaps) but more often than not because of our ignorance of the larger picture or the concentric circles of the stories of others around us. Our understanding of our own stories is inadequate but not without meaning.

Thus, any eye rolling at the number of coincidences in the book that I may have felt the urge to do was immediately squelched. My limitation. Not the book's. And Mazza wants us to know it--look how he titled the book. A Constellation of Vital Phenomena—the title comes from the definition of “life” in a Russian medical dictionary.

Yep, a constellation. Or a helix.

Now I have to curl up on the couch and read this one again.

------

Spiced Plum Jam

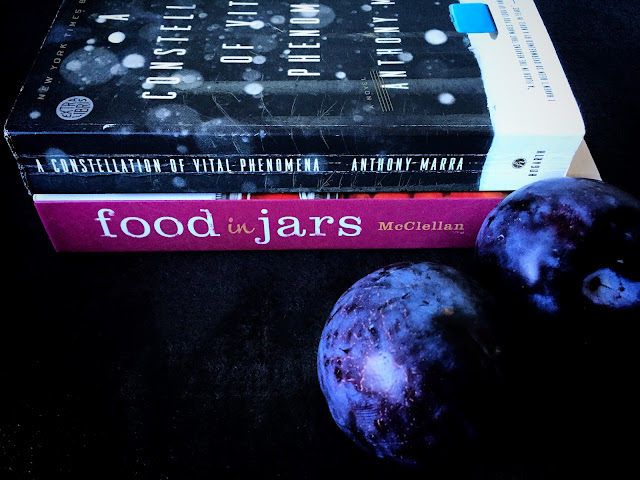

"Your father did many things in his forty years. Yet if pressed to recall his finest moment, I would chose to see him in the living room, with you, by the chess set peeling a plum" (A Constellation of Vital Phenomena 131-2).Adapted from Marisa McClellan's Food in Jars

This is the perfect fall jam. Make it every summer. Then slather it on everything you eat, including oatmeal, toast, or straight from the jar.

about 8 ½-pint jars

Ingredients

8 cups pitted and finely chopped plums (about 4 pounds whole plums)

3½ cups granulated sugar

Zest and juice of one lemon (preferably organic)

2 tsp ground cinnamon

½ tsp freshly grated nutmeg

¼ tsp ground cloves

2 (3 ounce) packets liquid pectin

Instructions

1. Prepare a boiling water bath and 4 regular-mouth 1-pint jars or 8 ½-pint jars (see To Sterilize the Jars below).

2. In a large stainless steel or enameled cast iron pot, combine the plums and sugar. Stir so the plums begin to release their juice. Bring to a boil and add the lemon zest and juice, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves. Cook the jam over high heat for 15-20 minutes until it looks quite syrupy and (as McClellan calls it) "molten."

3. Add the pectin and bring to a rolling boil for a full 5 minutes. The jam should look thick and shiny.

4. Fill prepared jars (see To Seal the Jars), wipe rims, apply lids and screw rings. Lower into a prepared boiling water bath and process for 10 minutes at a gentle boil (do not start counting time until the pot has achieved a boil).

5. When time is up, remove jars from the pot and let them cool completely. When they are cool to the touch, check the seals by pushing down on the top of the lid. Lack of movement means a good seal.

To Sterilize the Jars:

1. If you're starting with brand new jars, remove the lids and rings; if you're using older jars, check the rims to ensure there are no chips or cracks.

2. Put the lids in a small saucepan, cover with water, and bring them to a simmer on the back of the stove.

3. Using a canning rack, lower the jars into a large pot filled with enough water to cover the jars generously. Bring the water to a boil.

4. While the water in the canning pot comes to a boil, prepare the jam (or whatever product you are making).

5. When the recipe is complete, remove the jars from the canning pot (pouring the water back into the pot as you remove the jars). Set them on a clean towel on the counter. Remove the lids and set them on the clean towel.

To Seal the Jars:

1. Carefully fill the jars with the jam (or any other product). Leave about ¼-inch headspace (the room between the surface of the product and the top of the jar).

2. Wipe the rims of the jars with a clean, damp paper towel.

3. Apply the lids and screw the bands on the jars to hold the lids down during processing. Tighten the bands with the tips of your fingers so that they are not overly tight.

4. Carefully lower the filled jars into the canning pot and return the water to a boil.

5. Once the water is at a rolling boil, start your timer. The length of processing time varies for each recipe; for the jam, cook for 10 minutes at a rolling boil.

6. When the timer goes off, remove the jars from the water. Place them back on the towel-lined counter top, and allow them to cool. The jar lids should "ping" soon after they've been removed from the pot (the pinging is the sound of the vacuum seals forming by sucking the lid down).

7. After the jars have cooled for 24 hours, you can remove the bands and check the seals by grasping the edges of the jar and lifting the jar about an inch or two off the countertop. The lid should hold in place.

8. Store the jars with good seals in a cool, dark place. And jars with bad seals can still be used, just do so within two weeks and with refrigeration.

Probably much tastier than the jam I sent you. If you haven't yet read Elmet, you should. Then you'll have to base a blog post on bacon, whiskey, coffee and cigarettes. But it is a lovely book

ReplyDeleteThat book is on my list! Just got it, but haven't read it yet, but it is currently situated on my bedside table. And what, pray, is wrong with bacon-wrapped cigarettes with a little whiskey in your coffee?

ReplyDelete